In Austria inclusion excluded

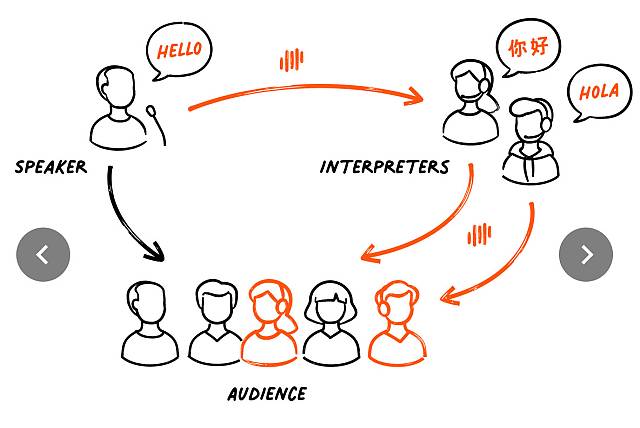

Inklusion ist eines der Anliegen der Smartphone-App und Website LiveVoice. Ihre Technologie des individualisierten Audio-Streamings erlaubt es, dass jeder Zuhörer eines Events die für ihn relevanten Informationen über das Handy oder den Laptop erhält. Anlässlich des Internationalen Tages der Muttersprache bat mich Julia Stockinger von LiveVoice im Februar 2024 zu einem Interview über den Stellenwert des Burgenlandkroatischen in der österreichischen Gesellschaft.

In an exclusive interview with Fred Hergovich, we discuss the profound role of the mother tongue in shaping identity and the challenges of preserving linguistic and cultural diversity in Austria.

On International Mother Language Day, we embark on an in-depth exploration of the captivating world of the Burgenland Croats – an ethnic minority living in Austria’s Burgenland region. But let’s start at the beginning: In the wake of the Ottoman wars of the 15th and 16th centuries, many Croats sought refuge as war-displaced individuals, migrating to other regions of the Habsburg Empire. The Habsburg monarchy actively encouraged this movement in order to repopulate the areas devastated by the Ottoman conquests. As a result, a part of the Croatian population found a new home in the Austrian Burgenland, mainly during the 16th and 17th centuries. Identified as the Burgenland Croats, this ethnic minority now numbers around 20,000, representing 5.9% of the total population of today’s Burgenland. But the number of people engaging with the language decreases at a fast pace as a consequence of Austrias assimilation agenda and the failure to treat language diversity as a treasure that must be preserved.

Their extraordinary history, language and culture are worth exploring, which is why we spoke to Fred Hergovich – an expert in the field and a Burgenland Croat himself. In this in-depth interview, Fred explores issues such as representation, recognition and the importance of respecting language and culture for their intrinsic value. Fred also reflects on the profound value he has discovered in reconnecting with his mother tongue, and candidly shares his insights into the challenges faced by numerically small ethnic groups when expecting recognition from the political realm. With a wealth of experience in the ORF’s (Austria’s public broadcaster) Croatian editorial department at the Burgenland regional studio and as head of the ethnic group editorial department, Fred provides a window into the Austrian media landscape and unravels prevailing attitudes towards ethnic minorities.

LiveVoice: What is your connection to the Burgenland Croats? How did you become an expert in this field?

Fred Hergovich: I was born in 1960 and grew up in the Central Burgenland in a village called Frankenau, or Frakanava in Croatian. In the 60s, it was common for Croatian to be spoken in schools and kindergartens, and in primary school, I learned German for three hours a week. In the 70s, there was a shift towards German instruction, especially in the northern Burgenland but for the first ten years of my life I mostly spoke Croatian.

Interestingly, my main German language buddy was a friend who visited Frankenau during holidays but spent most of his year in Vienna. His mother hailed from Frankenau, but life took her to Vienna after marriage. This friend, around my age, couldn’t speak Croatian, so our communication naturally shifted to German during his two-month summer stays. Additionally, the introduction of the first television in our household in the mid-60s played a role in my German language exposure. So, by the time I transitioned to grammar school in Eisenstadt at ten, I had to rapidly adapt to the German-speaking environment.

LiveVoice: It sounds like there were two worlds within the same country, quite isolated. Is that still the case?

Fred Hergovich: The landscape has evolved significantly due to media development and increased mobility. Until the 60s or 70s, Croatian was predominantly spoken in villages, influenced by the agricultural lifestyle. However, changes began as people sought jobs outside their villages, especially in Vienna. The trend away from Croatian accelerated in the 70s. Today, the conscious decision to speak Croatian is necessary, as German language dominance, especially through media, has diminished the Croatian-speaking community.

LiveVoice: How is the situation in elementary schools or schools in general? Is there still an option for Croatian language instruction?

Fred Hergovich: Since 1994, Burgenland has a Minority School Law requiring bilingual instruction in specific areas with a significant Croatian population. However, this legislation was introduced quite late, and by then, the decline in Croatian language usage was well underway. There’s a natural pressure from dominant languages, and despite legal provisions, the cultural shift has been significant.

LiveVoice: The language seems crucial for identity. Do you perceive it as a race against time?

Fred Hergovich: Absolutely, the decline is noticeable, but there’s a community of conscious Croats actively working to preserve their identity. However, there’s a substantial portion that feels indifferent or even believes distancing from Croatian is advantageous due to historical prejudices and disadvantages associated with the language.

LiveVoice: Can you elaborate further on that?

Fred Hergovich: You know how it goes in Austria – if something seems a bit unfamiliar, it can set off some alarms. Back in the school days, Burgenland Croats chatting in Croatian on the bus would sometimes get the harsh “Speak German, we’re in Austria!” treatment from their classmates. There is this unwritten rule that seems to apply more to certain languages like Slovenian, Hungarian, Arabic, or Turkish – not at all to English, French, Italian or Spanish speakers. And believe it or not, it still happens. Not too long ago, there was this right-wing politician, pushing for kids across the country to stick to German during school breaks.

LiveVoice: Why do people feel entitled to tell others in which language they are supposed to speak?

Fred Hergovich: While I might not be able to explain it fully from a psychological standpoint, I believe that there is a fear that partly stems from the fact that many people in Austria have had to adjust significantly in their childhood. It deeply threatens them when there are people around them who choose not to conform. This becomes apparent when someone speaks Croatian, Slovenian, Hungarian, Turkish or Arabic next to them. It feels threatening because they think ‘I have had to adapt all my life and now I expect complete assimilation’, particularly from individuals who are often marginalised by society. There seems to be a bias against those from cultures perceived as lower, creating this expectation of total assimilation. This attitude may stem from a deep-seated fear among many Austrians of the potential consequences of even a small openness to change.

LiveVoice: I’ve noticed that the Burgenland-Croats are not as visible in the media compared to other linguistic minorities in Austria. Why is that?

Fred Hergovich: It’s a complex issue. On one hand, Burgenland-Croats tend to assimilate to avoid drawing attention and potential discrimination. On the other hand, the official stance of the Austrian government plays a significant role. While laws protect linguistic minorities on paper, the genuine commitment to their preservation is questionable. The awareness and understanding of these linguistic communities are lacking, contributing to their invisibility in the broader Austrian context. Shockingly, they were not even represented in the House of Austrian History, the first museum of contemporary history in the republic, opened in 2018. Only after members of the Austrian ethnic minorities called the museum´s attention to the fact that they were completely ignored, the museum put up some additional pages on their homepage and amended the omission.

Besides that, one must acknowledge that democracy and our economic system always follow the majority. It is politically disadvantageous; you lose votes and approval when advocating for a group that is not numerically significant.

LiveVoice: It seems like there’s a struggle against assimilation and erasure. Is there anything that can be done to reverse this trend?

Fred Hergovich: The challenges are deeply rooted, and political efforts have been insufficient. While other countries like Switzerland actively support linguistic diversity, Austria has not prioritized the preservation of smaller languages. The lack of recognition and support has led many Burgenland-Croats to internalize the belief that distancing from their language is a path to societal acceptance.

LiveVoice: How is Burgenland Croatian actively used in everyday life? Are there still events or situations, perhaps in public spaces, where exclusively Burgenland-Croatian is spoken?

Fred Hergovich: Primarily within families. In public spaces, the use of Burgenland-Croatian is quite limited. There are specific associations and institutions, like the Croatian Center in Vienna or the cultural center KUGA in Großwarasdorf-Veliki Borištof, where there are events and where people engage in conversations in Burgenland-Croatian. Many music groups, especially Tamburica groups, exist, although their performances and communication often occur in German. Instances where only Burgenland-Croatian is spoken are quite rare.

When it comes to the media, the main platform for Burgenland-Croatian is the ORF (Austrian Broadcasting Corporation), extending into the public sphere. But it wasn’t like the ORF ever said, “Oh, it would be great if the Burgenland Croats had shows, and the Slovenes too, let’s support that.” No, it was more like with the Minority School Law or with the Official Language Law – individual Burgenland Croatians or associations had to go through years, sometimes decades of legal battles, all the way to the Constitutional Court. It was only then that the Republic decided, “Alright, the languages of the ethnic groups should be represented in schools, offices and courts. Although the ethnic groups did not have to go to court to get radio broadcasts, these programmes exist because they were imposed on the ORF. And it has always been this way, even today. It’s not something they embrace willingly; outwardly, they’ll say, “Great, we have these programs, you guys are the best.” But behind the scenes, everything is and has been done to make it palatable for the majority.

LiveVoice: You have been fighting for media representation for Burgenland Croats during your whole career. Were there situations where you faced challenges?

Fred Hergovich: I really enjoyed my job and it was great that I was able to do it. But you wouldn’t believe how narrow the boundaries in such a system can be. One example that illustrates the mindset is the music played in the Austrian Radio. Because we live in Austria, all radio stations were encouraged to play German-language music – I’m not sure if there was an actual quota, but that was the policy. And what’s happening now is that the regional radio stations are the ones that have the highest percentage of German music. So, there are older listeners who don’t speak English at all, and for them the emphasis on German-language music is quite natural. But similar to the national radio channels, it’s common in the regional studios to play English songs, occasionally an Italian, French or Spanish song. When I was head of our department, I often spoke to the director and the head of the music department. I pointed out that about 10 or 20 percent of Radio Burgenland’s listeners speak Croatian or Hungarian. I asked why we couldn’t play a Croatian, Hungarian, Roma or Sinti song from time to time. They reacted as if I had asked the worst thing in the world. Their answer was: “You have your show from six to seven, you can play them then”. This, in a way, encapsulates the official Austrian stance, at least at my workplace, which nobody perceives as racist or problematic – it’s just the way it is. Playing English, French, Italian or Spanish music is seen as international, but not Hungarian, Croatian, or Slovenian.

LiveVoice: Why is it so crucial for people that their music is represented on Austrian radio stations?

Fred Hergovich: I think it sends powerful messages that Croatian, Slovenian, or Hungarian music is part of our identity. In Austria, the classic expectation is that newcomers should integrate. However, the idea that we ourselves could change a bit to include others is rarely considered. There’s no thought given to the possibility that we could change ourselves and our structures to include others. My theory is that in Austria, there’s an extreme fear of what might happen if there’s even a slight openness, and that fear is at the root of racism.

LiveVoice: You told me that you didn´t speak your mother tongue during the eight years of grammar school. Why would you say it is personally important for you to have reconnected with Burgenland-Croatian?

Fred Hergovich: For me personally, it’s crucial because, in my twenties in Vienna, rediscovering and reconnecting with Burgenland-Croatian brought back strong memories of my childhood in Frakanava, which was deeply intertwined with the language. It allowed me to reconnect with my first 10 years in a beautiful way. Moreover, as I’ve been in retirement for three years now, spending more time in Croatia, I enjoy the positive reactions of people when they realize I speak their language. It’s a wonderful feeling when they acknowledge, “You are one of us,” even if only as a tourist. Moreover, it gives me the opportunity to feel just as at home in for example Zagreb, Split and even Belgrade as I do in Hamburg or Berlin. That’s a fantastic feeling.

LiveVoice: Thank you for this interesting conversation!